AKA the benefits of slow design.

Spend any time at a modern architecture firm, and you’ll quickly realize just how integral computer aided design (CAD) systems are to the process of creating and documenting any new project. From the earliest days of their integration, digital creation tools have elevated the efficiency and precision of the work done by architects and designers – but one seemingly antiquated method holds out despite. Through the flourishing of CAD tools, designers have always resorted to sketching by hand, even when designs are as complex as large-footprint building envelopes and specific architectural details.

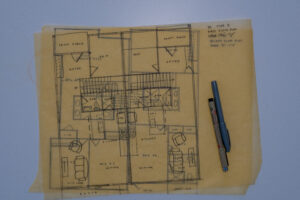

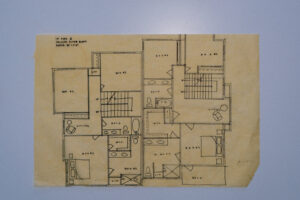

One primary driver here is the simple element of time efficiency, as few tools can replace the speed of quickly rendering an idea with pen and paper. The less obvious reason is the feeling of a hand-drawn idea. There’s an open-endedness to imprecise lines and flexible dimensions that keeps the conversation alive, giving both architect and client space to consider the decisions being made before things are set in stone. When sketching out a floor plan, you can give some extra line weight to the kitchen, just to emphasize the critical nature of that space, without belying the overall accuracy of the plans. This fluid nature baked into the analog method is key to the schematic stage of design, where the main ideas are molded and brought to life.

After the messier ideas are hashed out via analog means, the CAD software comes in to play, committing things to a far more accurate and repeatable state. But thanks to the looser strictures of hand-drawn ideas, that firmer reproductive method already has some life baked into it, setting the project off on the right foot.

All this to say, when a designer walks in with a roll of trace paper and a handful of pens, there’s more to it than simply being a well-curated accessory. This freer state of design is a key part of the language of design, and will stick around long into the era of computer design.